We had the pleasure of collaborating with the University of Queensland on this research project. Our collaborative work was published in the Journal of Anatomy, 2013.

To read the full article, please click here.

Also available online at PubMed.

J. Anat. (2013) 222, pp380–389 doi: 10.1111/joa.12020

Abstract

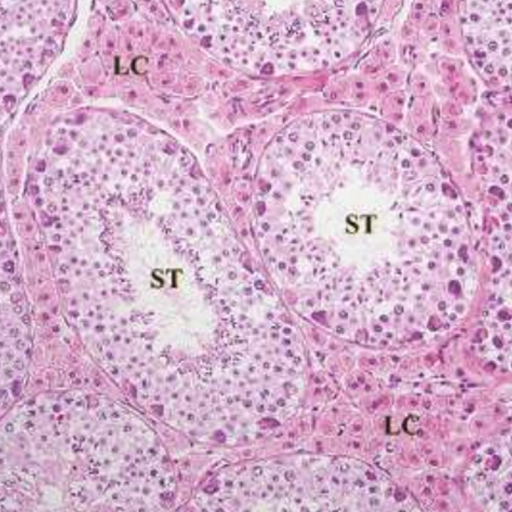

The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) and southern hairy-nosed wombat (Lasiorhinus latifrons) are iconic Australian fauna that share a close phylogenetic relationship but there are currently no comparative studies of the seminiferous epithelial cell or testicular microanatomy of either species. Koala and wombat spermatozoa are unusual for marsupials as they possess a curved stream-lined head and lateral neck insertion that superficially is similar to murid spermatozoa; the koala also contains Sertoli cells with crystalloid inclusions that

closely resemble the Charcot–Bottcher crystalloids described in human Sertoli cells.

Eighteen sexually mature koalas and four sexually mature southern hairy-nosed (SHN) wombats were examined to establish base-line data on quantitative testicular histology. Dynamics of the seminiferous epithelial cycle in the both species consisted of eight stages of cellular association similar to that described in other marsupials. Both species possessed a high proportion of the pre-meiotic (stages VIII, I – III; koala – 62.2 +/- 1.7% and SHN wombat – 66.6 +/- 2.4%) when compared with post-meiotic stages of the seminiferous cycle. The mean diameters of the seminiferous tubules found in the koalas and the SHN wombats were 227.8 +/- 6.1 and 243.5 +/- 3.9 lm, respectively.

There were differences in testicular histology between the species including the koala possessing (i) a greater proportion of Leydig cells, (ii) larger Sertoli cell nuclei, (iii) crystalloids in the Sertoli cell cytoplasm, (iv) a distinctive acrosomal granule during spermiogenesis and (v) a highly eosinophilic acrosome. An understanding of the seminiferous epithelial cycle and microanatomy of testis is fundamental for documenting normal spermatogenesis and testicular architecture; recent evidence of orchitis and epididymitis associated with natural chlamydial infection in the koala suggests that this species might be useful as an experimental model for understanding Chlamydia induced testicular pathology in humans. Comparative spermatogenic data of closely related species can also potentially reflect evolutionary divergence and differences in reproductive

strategies

Leave a Reply